Alright, let’s get a little cosmic.

In my first post, which set zero tonal precedent for this one, I mentioned the idea that there’s a fundamental tenet to our existence that we can’t ignore—something spiritual that pulls us toward things “larger than ourselves,” if you will. That’s not necessarily an explicit call to God, but an acknowledgment that we’re compelled to venture outside ourselves to satisfy that inescapable part of our being. So, what is that, then?

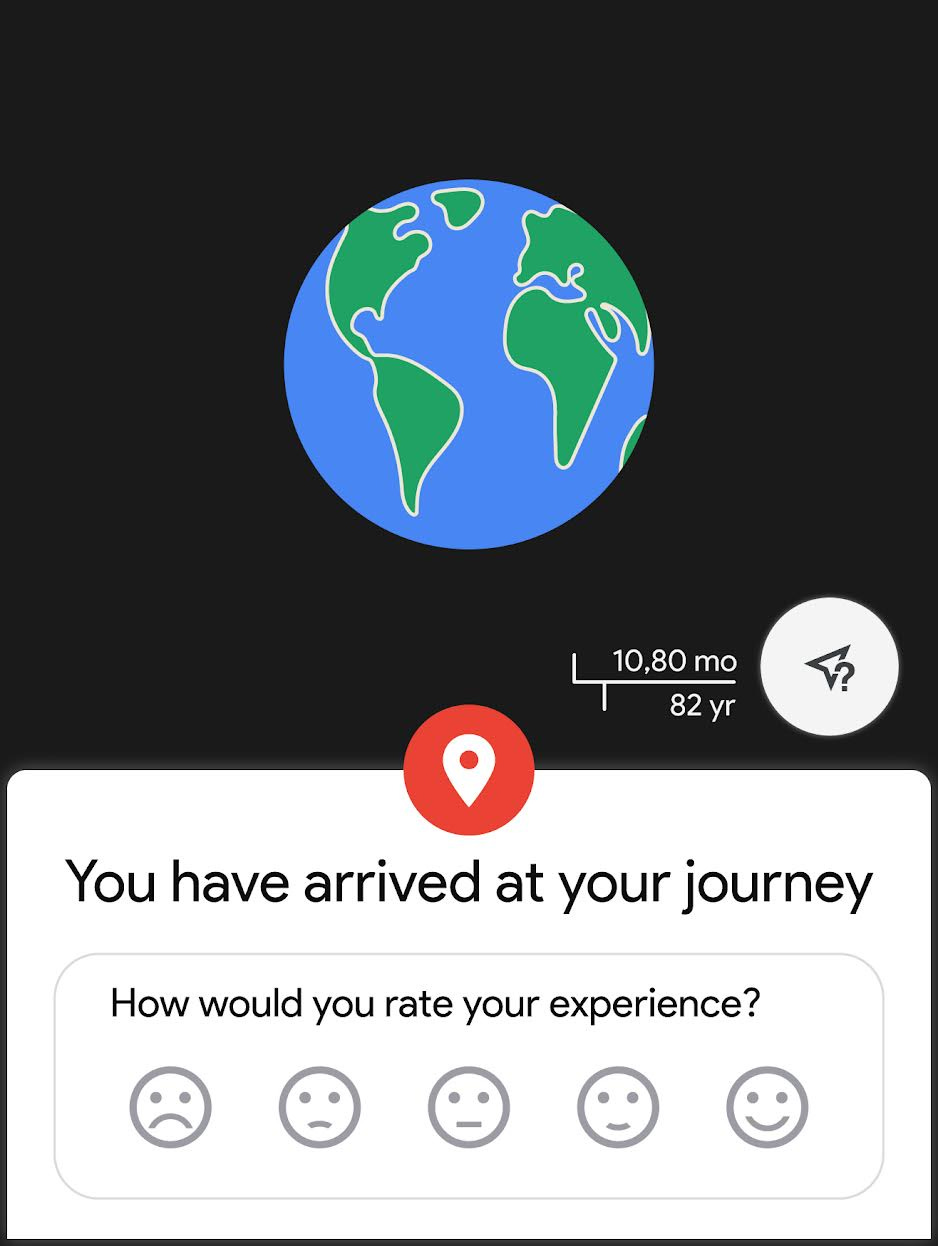

In this Substack, let’s call it “homesickness”—a sense that we belong elsewhere and must arrive there. To explore this idea, we’ll go through the Sufi poet Rumi’s work, Who Says Words With My Mouth?, piece by piece:

All day I think about it, then at night I say it.

Where did I come from, and what am I supposed to be doing?

I have no idea.

My soul is from elsewhere, I'm sure of that,

and I intend to end up there.

Whether it’s a relationship with the divine, the embrace of a romantic partner, or a dream career, we know there’s something we’re craving that we don’t quite have. A place where we’ll find completion.

And things just don’t feel right without it.

Not that we have a conscious reference for what we’re actually looking for, but we know this ain't it. In mysticism, there’s a general idea of oneness of all things and the suffering that perceived separation causes. To investigate what the “One” is and who we are, we’ll dive into the concept of nondualism through an Advaita Vedanta Hindu lens, though many traditions have similar concepts.

So what are we? Who is it that’s homesick to begin with?

In Hinduism, our personal existence can be described through the three bodies doctrine, capped off with the concept of Self.

First is the gross body—the least permanent part of our existence. It’s our physical form, starting at birth and ending at death. You get a new one every life, generally don’t treat it as nicely as you should, and it’s your vehicle for navigating the physical plane. Materialists generally identify with this level of form.

Next up is the subtle body. The subtle body is your mental and emotional form. It’s an energetic force that animates your gross body and is usually what people identify with when they think of their soul. In Advaita Vedanta, the individual soul is called jiva, which is ultimately an illusion. It’s the self-perceived soul one has when they’re aware of their metaphysical existence but haven’t yet attained their enlightened nature. For the general Abrahamic dualist, this is a pretty good stopping-off point for what we are. The mystics of those traditions, however, would be inclined to investigate further.

Now we’re onto the causal body. This one’s strange because it’s not really something that feels like “us.” It’s a storehouse of our karma—the algorithm of cause that allows us to exist as the effect. Karma literally means “action” and is simply the aggregation of happenings begetting further happenings. As the causal body runs its program, our subtle bodies can transmigrate to gross bodies, allowing our jiva to continue its journey through the realms of rebirth and existence, or Samsara, as they call it in the Dharmic traditions.

So, which one are we?

None of them... and you may not like the actual answer.

To continue where Rumi left off:

This drunkenness began in some other tavern.

When I get back around to that place,

I'll be completely sober. Meanwhile,

I'm like a bird from another continent, sitting in this aviary.

The day is coming when I fly off,

but who is it now in my ear who hears my voice?

Who says words with my mouth?

This is where the idea of Self comes in. God, the Self, or Atman, is the experiencer of consciousness. Through the perfect amnesia provided by the causal body, the sense of individuality experienced with the subtle body, and the limitations of the gross body, God can adventure through Samsara as all of us without breaking the suspension of disbelief.

Who said words with Rumi’s mouth? Who is it that says words with this Substack? The same one who reads it a thousand miles away. My friends, there’s one of us. Which is to say, there are two perspectives:

You are not real

You are the entirety of reality

You’re free to take your pick, my friends.

Your ex that you can’t stand and your favorite pet are both God playing make-believe, as are you. In the endless cycles of reincarnation, everyone has been your mother, everyone has been your child, and all of you were just the same “guy” to begin with. This game is called lila by the Hindus, translating into “divine play.”

So, what are we even doing here?

Well, it’s nice. I like it, anyway. And I’m God, so my word is final.

But on a serious note, things can only “exist” within dualism. In absolute reality, there’s absolutely nothing that can happen because subject and object, observer and observed, are simply not manifested. In the Abrahamic tradition, Eve was created from Adam’s removed rib. A creation in dualism within his reality allowed him to experience companionship and a return to oneness in marital embrace—or, to quote the Bible: “and they shall become one flesh.”

Yes, I know, they started as one flesh. It sounds rather inconvenient that in order to return to where Adam started, he needed to wine and dine Eve, but this was the only way for love and companionship to fully manifest and be expressed.

So, about that homesickness...

Continuing Rumi’s poem:

Who looks out with my eyes? What is the soul?

I cannot stop asking.

If I could taste one sip of an answer,

I could break out of this prison for drunks.

I didn't come here of my own accord, and I can't leave that way.

Whoever brought me here will have to take me home.

Now, onto the concept of home. It’s talked about everywhere by everyone.

Baba Ram Dass said, “We’re all just walking each other home.” The story of the Torah is about the Israelites journeying home. The Quran says we’re all returning. Where is it we’re returning to? I’ll give you a guess.

In the realms of dualism, the only thing that isn’t some level of illusion is the place within you that is nondual with all that is “external” to you. “Namaste” is an acknowledgment of that, meaning “the divine in me honors the divine in you.” Once that divinity truly emerges from its karmic cocoon, you’ll see it’s not just a figure of speech.

Enlightenment: the realization you’ve been home the whole time.

As the Upanishads puts it: “To the seer, all things have verily become the Self; what delusion, what sorrow, can there be for him who beholds that oneness?” Identifying with the Home, rather than with the feeling of homesickness, is all it takes to achieve peace. To realize that you and home are one and the same—that any sense of separation is simply the illusion that makes the game playable.

The journey home is instantaneous and requires no change in location, as if you’ve been in your living room all along and you’ve finally remembered to turn on the light. The secret we’ve been hiding ourselves from is that we never left, a truth buried in a tangle of identity and hang-ups.

To conclude Rumi’s poem:

This poetry, I never know what I'm going to say.

I don't plan it.

When I'm outside the saying of it,

I get very quiet and rarely speak at all.

When Rumi disidentifies with the saying of those words, when he is doing without identifying as the doer, he glimpses his true nature and loses the need to speak. Because once you remember what you truly are, where you truly are, that homesick urge evaporates and you just are.

You are here. You are it. No more is needed from you. No effort to be is necessary. If we let go of a bit more of our self-grasping each day, dance with the situation of our existence rather than wrestling with it, that feeling of home will grow, and the sense that something isn’t right will transmute into clarity.

And if that’s not something easy for you to do, that’s alright. We can play here in the realms of make-believe a little longer. Whoever brought us here will most certainly come to take us home.